Religion at the Crossroads of Intersectionality: Femonationalism and Islam Today

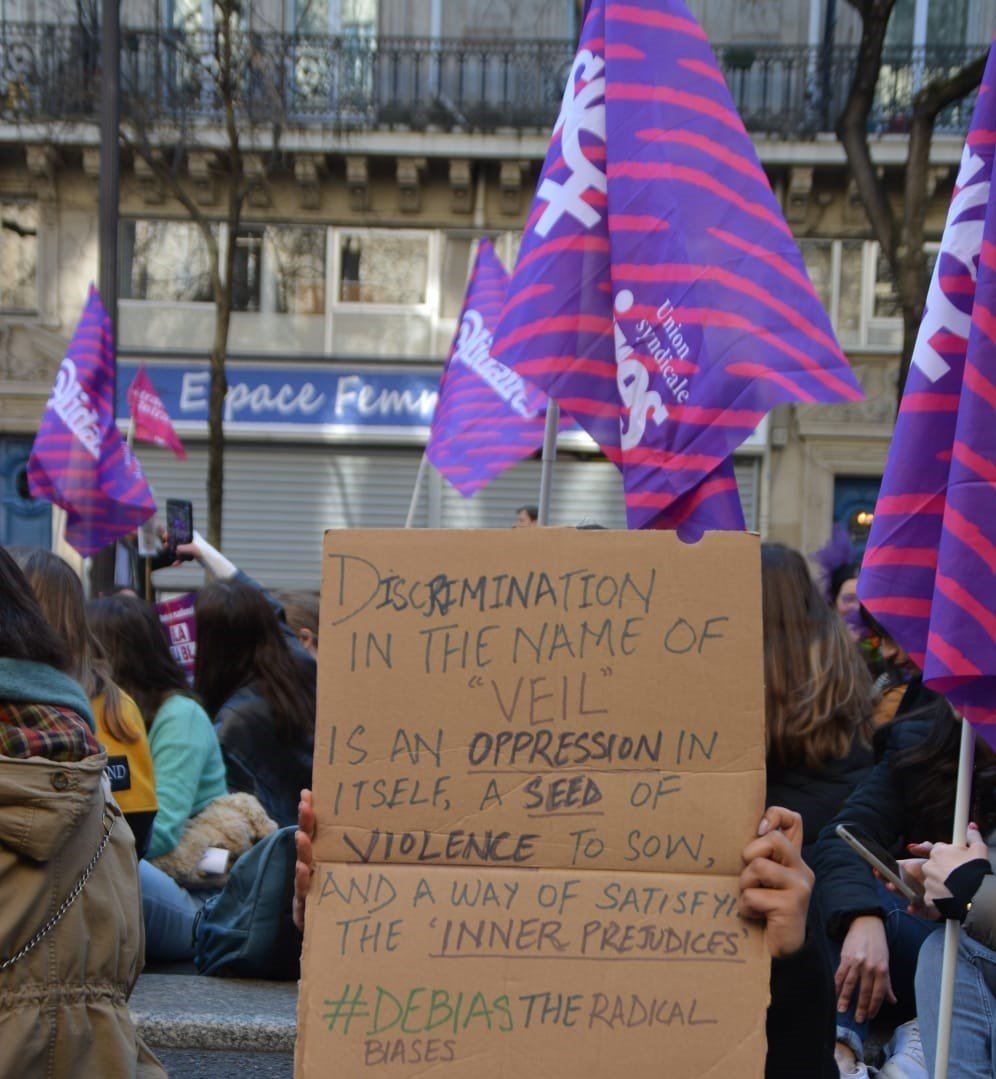

Muslim women have constituted a burgeoning segment of the immigrants in the Global North residents of the United States (US), Germany and France have been subjected to racial and religious discrimination. Laws and regulations such as the burqa ban, the banning of head scarves and full face highlights the measures taken to discriminate Muslim women. The introduction of such legislation curtails Muslim women’s access to education, jobs and social programs. These have become particularly pertinent in light of the recent executions over anti-hijab protests in Iran.

At the roots of these legal frameworks is often a phenonemon called femonationalism, which combines nationalist ideology with feminist ideas to justify racist and xenophobic views. It is often structurally embedded into political frameworks, (foreign policies) which has resulted in rising social inequalities for marginalised communities. The real challenges of inequalities are based on several factors – this includes being a woman of colour, embracing a different religion, and being regarded as an immigrant who is categorised as an ‘alien’. Hence, this significant triad of race, religion and gender needs to be framed into an intersectional perspective to highlight the existent structural systemic inequalities.

Neoliberal Globalisation and the Triad of Intersectionality

Reaching everyone around the world is a stark motivation behind the ideology of ‘intersectionality’,

which is a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw. Intersectionality is seen through the lens of the segmentation of people of color, queer and transcommunity. The objective is to overcome the structural societal ploys of patriarchy, capitalism, and racism. The original notion of intersectionality stems from the inability to deliver justice through the courts. Contextually, in 1976, black women were being rejected for job applications because of General Motors’ biased selection for either white women or black men when it came to filling certain jobs. This highlighted the considerable neglect of complexities within the system and an institutional failure to acknowledge intersectionality.

Often, discrimination and exclusions based on religion –especially when referring to Islam– are racially charged. Nationalist-xenophobic policies are often driven by the constellation of religion, race, and gender, while also fusing religion and race on the discourse of being different, threatening and naturally backward according to Crenshaw. However, it is not only national legislatures that struggle with being sexist and racist. White male dominance prevails in multilateral institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Their development policy frameworks involve the control and regulation of capital funds, currency stability management or the trade development. These policies have reconfigured labour markets and exacerbated nationalist-xenophobic policies promoted by right-wing politicians in the Global North. This, in turn, has disproportionately affected migrants and marginalised communities who lack access to welfare systems, labour market, and healthcare.

Femonationalism and Feminism as Constituent Elements of the War on Terrorism: Islamophobia in Context

Femonationalism is a debate that stems from the heterogeneous anti-Islam and anti-male immigrant mandates of nationalist parties. Femonationalism paints Islam as ‘radical’ to justify the prejudice and stigma against Muslims. It must be understood from an intersectional perspective because the arguments Femonationalism employs operate on multiple intersections. One argument that has emerged in feminist discourse especially since the 1990s calls for liberating Muslim women through the adoption of ‘European Femininity’. Despite other voices critiquing the demonization of Islam as a misogynistic and patriarchal religion and culture, which allows white men to ‘save’ brown women from brown men, this argument persists.

Islamophobia is used to forge the belief that all Muslims are religious fanatics and have violent tendencies towards non-Muslims. For example, to pursue their vested economic and geopolitical interests, the US and Europe had propagated Islamic fundamentalism and Islamo-fascism by waging wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and supporting Israeli assault in Lebanon and Gaza. Consequently, the 9/11 rhetoric during the Bush administration’s war on terror was penetrated with Islamophobic assertions, which is also when femonationalism came into play. The feminist ideology – which was aligned with the US imperial project – supported discriminatory attitudes, arguments and policies in the name of the ‘emancipation of women’, which was thought to bring modernization and democratisation in Afghanistan and Iraq. Thus, the nexus linked democracy, free markets, and the emancipation of women. It was this rhetoric that, according to Hester Eisenstein, associated terrorism with patriarchy while claiming that Islamic values were associated with traditionalism and pre-modern culture.

Migrant Women: The Silent Force Behind White Women

As a result of femonationalism, Muslim women have faced extreme danger and vulnerability. The rise of imperial right-wing forces – which have incited honor killings, forced marriages and the wearing of hijabs – has unintentionally highlighted the supposed ‘differences’ in Western and Islam- based cultures. This has presented a seemingly irreconcilable assimilation of Muslim immigrants in the Global North.

A Muslim migrant woman is assumed to be given a ray of hope through ‘workfare’, a form of welfare which ties work to receiving aid under the blanketed notion of good labor market opportunities. These policies are seen as justified because they supposedly enable women to work and to feel liberated. However, what ensues is that migrant women are employed in precarious, low paid jobs mostly in the care and domestic work sectors for tasks such as housekeeping and caregiving. These often overqualified, migrant women workers play an important role in providing gateways for white, civic and class privileged women to foster their careers. From a Marxian perspective, these women serve as the invisible labour who maintain the well-being of European families and individuals.

‘Intersectionality’ as a Manifesto

As a whole, religion is a layer that needs to be explored through an intersectional lens. The triad of race, religion and gender depicts how these dimensions are politically and socio-economically embedded as part of Western culture. Through ‘femonationalism’, the intersectional approach towards highlighting inequality becomes prominent. It needs to be seen as a guiding perspective to identify the systemic inequalities (socio-economic, immigration and race) that exist in the name of ‘religion’ under the guise of geopolitical and economic interests. Most importantly the outcry of this discourse to be problematic for the women with intersectional identities seen as a ‘threat to European civilization’, and suffer through hate crime and unfair dismissals from within the institutional spheres. Hence, posing a simple question of “whether the nationalist policies are by any means liberating OR rather entrapping these women in chain of religion spurred racialized cycle? restricting the ‘freedom of choice’ which is strictly associated with her identity, and making her more marginalised when she chooses an identity of being a ‘Muslim immigrant woman of a color’?”

References:

American Civil Liberties Union. 2008. Discrimination Against Muslim Women - Fact Sheet. [online] Available at: <https://www.aclu.org/other/discrimination-against-muslim-women-fact-sheet> [Accessed 16 July 2021].

Bonhomme, E., 2019. The Disturbing Rise of ‘Femonationalism’. [online] The Nation. Available at: <https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/feminism-nationalism-right-europe/> [Accessed 30 July 2021].

Eisenstein, H., 2009. Feminism Seduced: How Global Elites Use Women’s Labor and Ideas to Exploit the World Herndon. Virginia: Paradigm Publishers.

Farris, S.R., 2012. Femonationalism and the" Regular" Army of Labor Called Migrant Women. History of the Present, 2(2), pp.184-199.

Fekete, Liz. 2006. "Enlightened Fundamentalism? Immigration, Feminism, and the Right." Race and Class 48 : 1-22.

Fenner, A., 2020. “Reach Everyone on the Planet…”: Kimberlé Crenshaw and Intersectionality.

Gerards, J., 2013. The discrimination grounds of Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Human Rights Law Review, 13(1), pp.99-124.

Gutierrez, M. ed., 2003. Macro-economics: Making gender matter: Concepts, policies and institutional change in developing countries. Zed Books.

Nations, U., 2021. Universal Declaration of Human Rights | United Nations. [online] United Nations. Available at: <https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights> [Accessed 1 August 2021].

Samour, Nahed., 2019. Kimberlé Crenshaw at the German Federal Constitutional Court: religion at the crossroads between race and gender. Heinrich Boll Stiftung Gunda Werner Institute. Available at: https://www.gwi-boell.de/en/2019/05/27/kimberle-crenshaw-german-federal-constitutional-court-religion-crossroads-between-race

TRT World. 2021. Stabbed under the Eiffel Tower: How France's deradicalization hurts Muslims. [online] Available at: <https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/stabbed-under-the-eiffel-tower-how-france-s-deradicalisation-hurts-muslims-40797> [Accessed 1 August 2021].

Weichselbaumer, D., 2020. Multiple discrimination against female immigrants wearing headscarves. ILR Review, 73(3), pp.600-627.

About the author:

Maria Syed is a former Erasmus Mundus Scholar from Pakistan. She holds a Masters's degree in EPOG+, an interdisciplinary program specialized in macroeconomics, global governance, and socioeconomic transition. She is currently based in Berlin where she works as a feminist macroeconomist consultant on fiscal justice agenda at Third World Network. She is a volunteer, traveler, artist, and change-maker.